How great design harms us and why art is the answer.

*“All you young people are **brainwashed *by design”, calmly provoked my neighbour. Not quite the reaction I expected after proudly showing off my renovated bathroom.

“All I had growing up was a single room for sittin’, cookin’, washin’ and cleanin’, that’s all you need…these interior’ design magazines’ just make people miserable”, he exclaimed.

Though my neighbour’s response lacked the accolades I sought, perhaps he had a point. Technically I’m also complicit in contributing to this problem of ‘brainwashing’ through design.

My job as a product manager involves using design to craft an experience you couldn’t imagine living without. Being successful means I’ve created something that makes you feel in control and in return demands your attention.

“Fear is a relative thing; its effects are relative to power.” — Sarah Hall, Novelist

By providing us with options or opportunities for a better experience, design sometimes makes us feel we are no longer living our best lives. For example, a newly announced phone that takes photos in the dark is not selling us on a better camera. Instead, it makes us realise all the moments with family and friends we currently fail to capture. How much are those precious memories worth to us? Without this new tool, we can feel relatively deprived and that we are no longer living our best lives — a relative deprivation.

Perhaps we are better off living with ignorance. To paraphrase Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan “a fish doesn’t know what water is until it’s been beached”. It’s like losing your wallet — that’s bad enough. But sometimes, just the knowledge that you lost something is so painful we wish we could forget we ever had that thing in the first place.

The relative deprivation provoked by design is not just a painful reminder of how much less we have, but actually, a reflection of how uncomfortable we are with less control. What we should be aiming for is a better understanding of this relationship with design, how it affects us and what we should be practising to make things better.

Our unhealthy relationship with control

Product design is about solving a problem so painful people would pay to make it go away. We achieve this by effectively giving our users new types of controls. But what we fail to realise is that sometimes just by simply providing those controls, only then do we recognise how painful our problems really are.

A fish doesn’t know what water is until its been beached.

Twitter, for example, is not just a service that allows us to express ourselves but also one that provokes outrage while demanding your response. Twitter’s design both shows us how little control we have over the world, then offers us a solution to try and control it.

To illustrate how design changes our perspective of the world, a tree, for example, is no longer just a tree. Design reveals all the inherent possibilities of that tree becoming a table, paper, or an oat milk carton. We can never simply appreciate the tree again; we are instead on some level always compelled to consider it as an underutilised resource.

“Calling a spade a spade never made the spade interesting yet. Take my advice, leave spades alone” — Edith Sitwell, British poet

Understanding this is valuable because we think of design as something we do onto the world, but the objectivity of design can just as equally influence and objectify us. The optionally presented to us through smartphones, apps and services can’t help but seize our psychology through the powerful controls it provides.

Perhaps my neighbour’s inconsiderate bathroom comments were so confidently delivered because he has really taken the time to reflect on what helps him feel in control of his life. So what could we be doing to achieve a similar type of thinking? What should we be doing to help the users achieve a similar type of thinking through our designs?

Technology “makes us think about the world informationally and make the world we experience informational” Philosopher Luciano Floridi once noted. Put another way, “we should consider what kind of person a new tool of control may lead us to become. What habits of thought and attention are we cultivating by engaging with any specific technology?”1

Rethinking our relationship with design starts by reviewing our relationship with control. It may require accepting that we may not be able to control everything, but at least we can decide what controls should hold power over us.

Using design to escape control

Though the intention of design may be to create pleasurable experiences, it does so best when it enables us to exercise control of our environment and our emotional states.

“When a person can’t find a deep sense of meaning, they distract themselves with pleasure.” — Viktor Frankl, Austrian neurologist

Social media, video streaming and productivity services are always available with entertainment or tasks to appease our restless minds. We live in what german philosopher Walter Benjamin called (almost 100 years ago) a “constant state of concentrated distraction.” Quiet moments in an age of distraction can paradoxically feel like our minds shouting at us. We could always be using our time better for pleasure, learning or making money instead.

Philosopher Erik Fromm who wrote much on freedom would find this state of anxiety induced by our multitude of choices familiar.

Fromm in his book The Proper Study Of Mankind described **two *types of freedom in this world: *positive and negative freedoms. Negative freedom represents the chains of things holding us back like money, laws, communication, location or knowledge. Some could argue that thanks to inventions like democracy, infrastructure, access to capital and the internet, more of humanity than ever before has been unshackled from this negative freedom.

A good thing, right? In many ways, this represents tools like design working to enable our autonomy and control. Fromm would agree, but he would also say that removing all the negative freedom in the world is useless unless combined with a healthy dose of positive freedom — the freedom to choose to do positive things. You can cut all the chains holding you down, but if you have nowhere to go, then what was the point?

To quote Kierkegaard, “anxiety is the dizziness of freedom.” We now find ourselves in this uncomfortable place — on the one hand, free from our chains to take action, but on the other totally independent. Without intention to positively connect with the world using our tools of control, it leaves us vulnerable to those tools controlling us.

Recall our tree example from earlier. German philosopher, Martin Heidegger states that technology makes us see nature as a standing reserve of resources, but technology can also turn us into a resource. In her book Nihilism and Technology, Author Nolen Gertz argues that our desire to control things is how we fall prey to designs instrumental framework.

A bucket, for example, can only be understood by thinking about what we use it for. Make that bucket available to people without direction, and suddenly we start thinking about how those people can be utilised.

In the same way, I’m sure nobody at Twitter or Facebook intentionally designed their experience to encourage trolling or doxxing; app features like feeds, trending news, and messages compel us (the users) to take control. We generate the data and behaviours to operate more efficiently, and without practising positive freedom we live in ways that serve not our goals but those of design to engage us.

For Heidegger, the point is that technology and design has a logic of its own beyond human intention. What it reveals about ourselves and humanity is not always going to be up to us.

Without reflecting on how we choose to exercise positive action on the world (positive freedom), the vacuum of insecurity and desire to keep control compels us to continue serving the goals of technology. Instead, we should be seeking to build better relationships with the design that empowers users of that technology.

Roger Martin, former Dean of the Rotman School of Management, would suggest developing systems that force us to slow down and pay attention — like a road sign warning us about a crazy roundabout. It doesn’t matter if it’s a personal system or one baked into a product, the point is that the solution provides time for us to consider the complexity of our options.

In our aim to create things, we should always seek to use our freedom to help others achieve success based on their self-chosen growth and happiness. In practising this process of slowing down, our first step is to consider seeing the world from different perspectives. Luckily, art may be one of the best tools we have to achieve this.

Art will save our souls

So how can we create a better relationship with design? Heidegger would suggest we should spend more time appreciating art.

Heidegger believed that art, in particular, reveals aspects of the world that are inaccessible to a scientific or technological approach. Art forces us to recognise that there are many abstract ways of framing things and invites us to see the world differently.

In The Mathematics of Love, author Hannah Fry explains that by allowing yourself to view the world from an abstract perspective, you create a language that can uniquely capture and describe the patterns and mechanisms that would otherwise remain hidden.

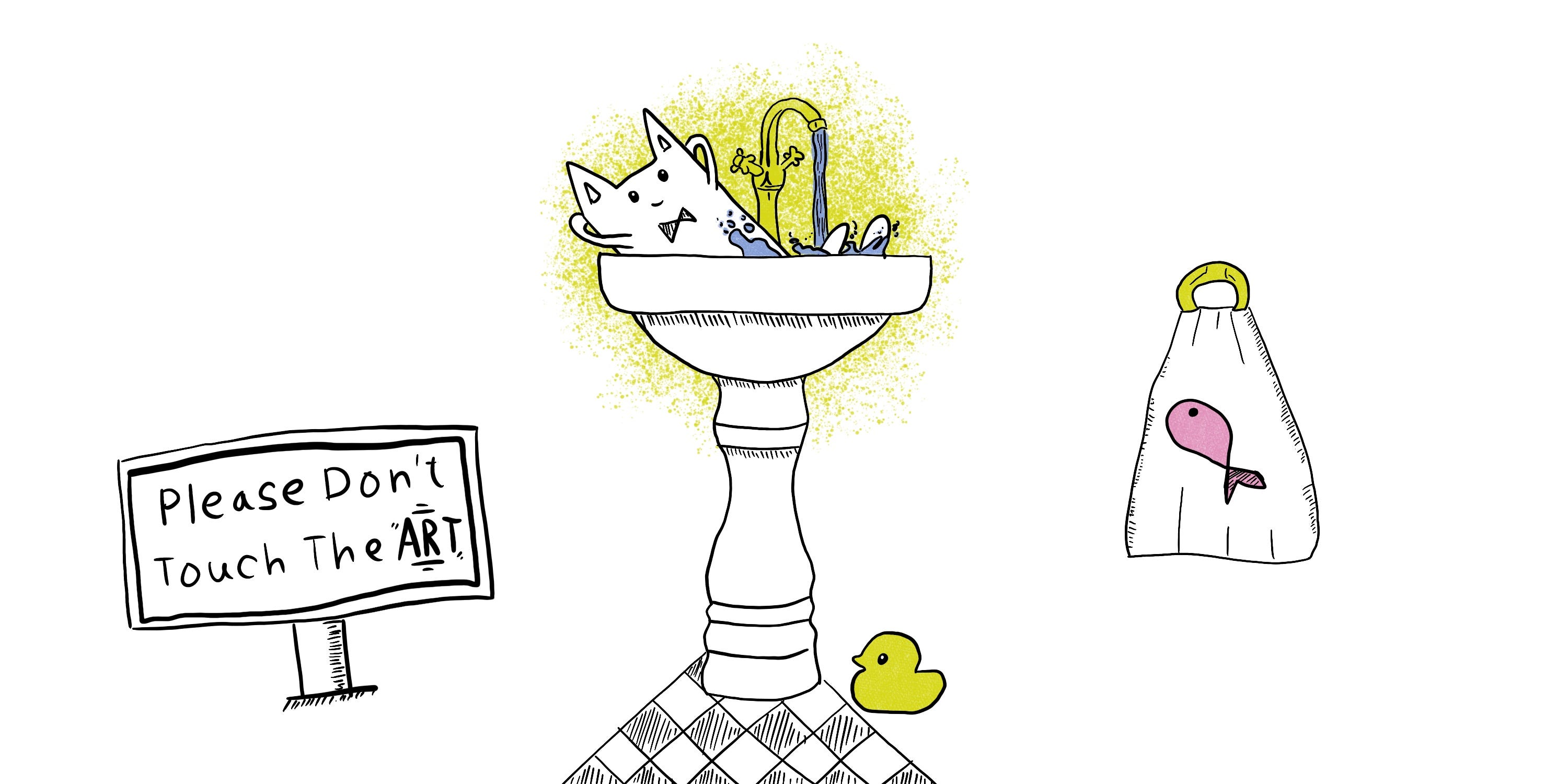

Let’s say I offer to build you the world’s most extraordinary bathroom — it has a high-pressure shower, golden mosaics, underfloor heating, cosmetic refrigerator, the works. Upon completion, I forbid you from using this bathroom. I go as far as to place a strip across the entrance that reads ‘Do not touch’. Desperately you turn to me and shout, “What are you doing?” Calmly I respond, “I promised to build you a bathroom, but never promised to let anyone use it.” And just like that, I have stripped this room of all utilitarian function and freed you to see it differently. It is no longer simply a collection of things to use but has the opportunity to reveal something more meaningful to you.

“The whole point of art, as far as I’m concerned, is that art doesn’t make any difference. And that’s why it’s important” — Kevin Kelly, Editor Wired Magazine

“The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera” famously remarked photographer Dorothea Lange; that’s very much the point here. To paraphrase writer and researcher Dan Nixon, “design and technology should serve instruments that teach us how to see the world more fully, not only with technology but also without technology.”1

Tech researcher Evgeny Morozov would argue that achieving this mindset “requires us to usher in a ‘post-solutionist’ tech paradigm. It is incumbent upon us — users, designers and engineers — to ask ‘what if’ and ‘why not’ about the possibility of technologies. To paraphrase Nixon again, “Design in itself is neither the problem nor the solution. Designed experiences should in themselves support a continual spirit of questioning from its users.”1

“Artists have always faced this issue: the world is immense, so what slice can evoke the whole cake?” — Lincoln Perry, Artist

Heidegger and others like him would want us to realise that there are ways of seeing the world that doesn’t rely on design’s prism. That paradoxically the solution is appreciating that we will NEVER fully control how design influences us, but that doesn’t require us to be bound by design’s intentions either.

Without being able to slow down and view things pluralistically, there will always be a danger as author Kate Crawford states in her book Atlas of AI, that the things we create may invariably amplify and reproduce the forms of control we intended to solve.

Crawford tells us that AI should interrogate the power of structures in which it is embedded, especially when those structures involve equality, justice, and democracy. I believe the same approach should apply to any kind of designed entity.

As individuals building the products of tomorrow, we have a responsibility to consider how our designs impact our users. How design both provides control yet makes us feel helpless, how new controls influence our perspective of the world, and finally, how design at its worst makes us see people more like resources than people.

We may not be able to escape the brainwashing of design entirely, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing either. All we may need to do is simply reflect on how much we choose to be controlled by it.

If you enjoyed the ideas discussed in this article and want to learn more please check out the list of references below and send the authors there some love.

“Just like it is the Pope’s job to bring religion closer to today’s technology, it is our job to bring technology closer to the humanities.” — Brad Smith, Microsoft president

Want more? I found reading the following articles a great source of inspiration for this article. Thanks so much everyone!

- What is this? The case for continually questioning our online experience, Dan Nixon

- The Role of the Arts and Humanities in Thinking About Artificial Intelligence, John Tasioulas

- Do We Control Tech — Or Does Tech Control Us?, Alexis Papazoglou

- Machine learning has uncertainty. Design for it., Mark Myslin

- Frankfurt School — Erich Fromm on Escape from Freedom (Podcast), Steven West

- Against Persuasion, Agnes Callard